“The inhabitants of the upper Italian valleys to the south of Monte Rosa have a widespread tradition of an enchanted valley, beautiful and rich, which once existed in the heart of the mountain, and has now disappeared…”

-from The Scenery of Switzerland and the Causes to which it is Due (1896) by Sir John Lubbock

There is perhaps no other place on earth more mysterious, more sublime, more transportive than the mountaintop. Like oceans, which in pre-modern times were sectioned into known and “here be dragons” territories, mountains were chimeric, part reality, part fantasy. Ordinary life carried on as usual in highland regions and valleys, but the uninhabited, scree-clad hinterlands and snow-worlds above the clouds were the domain of the imagination. Here the elements, like eldritch immortals untempered by earthly technology and ambition, were truly indomitable. Accordingly, the most precipitous and wayward peaks, comprehended only in speculation, were veiled in myth.

Early writers described the lofty mountain as a kind of bridge, a medium through which a divinely favoured person could directly commune with the gods on high. During this communion, the human contactee would, like Moses on Mount Sinai or Jesus at the site of his transfiguration, suddenly become fearsome or awe-inspiring in aspect.

As time went on, however, mountains gradually became more associated with the so-called Luciferian “powers” of the upper air. To paraphrase Heinrich Heine: “All Olympus was transformed into an airy hell.” In the Medieval mind, mountainous regions evolved into “here be griffins” precincts of weird and wicked happenings. As such, they were reserved for aberrant, apostical persons, the sort who liked to raise storms, smite livestock, and–on certain nights–knock boots with Old Nick himself.

One of the most well-known of these cloud-capped otherworlds was Mount Pilate. Said to be the resort of dragons and tempest-raising demons, it was also where sorcerers travelled to consecrate their grimoires. The Venusberg, another mythical mountain first elaborated in Medieval-era texts, was also believed to be a centre of diablerie. Ruled by a distorted version of the Roman love goddess, it harboured an infernal pantheon of lesser fiends and succubi who loved nothing better than to lure wayward knights away from the Christian path.

Such tales of magic and wonder eventually went on to inspire many a Romantic poet. In Lord Byron’s Manfred (1813), the titular character–a suicidal magician–ascends Mount Blanc in order to summon a host of spirits, including the oracle-like “Witch of the Alps”. Similarly, in Johann Wolfgang Goethe’s Faust, Part Two (1832), the Harz Mountains – as per a long-standing literary tradition – serve as a stomping ground for witches and ogreish “wild men of the woods”.

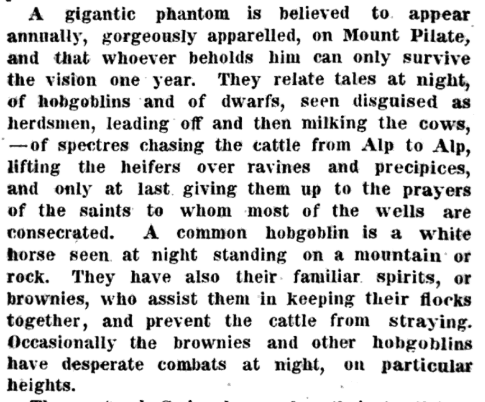

By the nineteenth century some aspects of Alpine-centric narratives had also merged with local oral traditions. In My Note Book: Switzerland (1837), the Scottish historian and politician John MacGregor said that the “people of the Alps” believed in a number of legendary monsters, including sheep-eating hobgoblins and “mountain Genii” who conjured up storms and attacked herdsmen. Macgregor also maintained that a “gorgeously apparelled” phantom was said to appear once a year at Mount Pilate. Much like the mythic mortal Semele who was burned to a crisp after witnessing the true form of Zeus, anyone who ventured to look upon the demon of Pilate would be doomed to suffer an untimely death.

Like Macgregor, the English geologist Thomas Bonney also wrote about Alpine supernaturalism. The Alps, he maintained in The Alpine Regions of Switzerland and the Neighbouring Countries (1868), were believed to be home to “a vast multitude” of imps and “spectral animals”. Possibly the most frightening member of this ghostly assembly was an undead goatherd who was struck by lightening in retribution for forcing his flock to worship a crucified he-goat. “And now,” said Bonney, “he wanders forever over the Alps, miserably wailing.”

Although it lacks diabolic elements, the lesser-known legend of the lost valley of Hohen-Laub (or Hohenlauben) is equally interesting. The anecdote first appeared in the third volume of Voyages dans Alpes (1796), a book by the Swiss polymath Horace Bénédict de Saussure. According to Saussure, an “ancient tradition” held that Hohen-Laub–once an sunny district of rolling pastures in the heart of the Italian Alps–had been separated from the rest of the outside world by a wall of freshly formed glaciers. In 1789, an old priest encouraged a group of men from the town of Gressoney to investigate. The adventurers departed shortly afterwards, spending the night in Monte Rosa’s upper reaches. The following morning they trudged through the snow for hours until they came to a high promonotory overlooking a vast gorge.

“There,” wrote Saussure, “they saw beneath their feet, to the north, a valley surrounded by glaciers and frightening precipices, partially covered with the debris of rocks and split by a stream which watered superb meadows, with green woods in the depths of it, but without any sight of human habitation or of the presence of domestic animals.” Convinced that what they were seeing was the fabled lost valley, the mountaineers subsequently wrote to the Court of Turin to alert the proper authorities.

The group embarked on another expedition two years later, this time with the aim of exploring the lost country. Mother Nature, of course, had other plans. Their crampons, ropes, and ladders, were useless on the terrain. Failing to “make any success”, the team returned home, bemoaning the “prodigiously high” cliffs.

In his analysis of the Hohen-Laub legend, Saussure conjectured that the mountaineers had really seen Pedriolo, a sparsely populated, grassy stretch of land in the nearby valley of Macugnaga. “If,” he wrote, “we consider that the Pédriolo chalets are in the lowest part of the valley, furthest from the gorge, and behind rocks which completely conceal them from the view of the southern peaks, we will understand that if the herds were grazing in the pastures to the north below the chalets, at the time when the Gressoney hunters came for the first time along the edge of this gorge, they must have seen neither habitat nor herds in this valley.” Nevertheless, despite Saussure’s attempts to explain it away, the Hohen-Laub episode went on to inspire at least three more independent expeditions, none of which did anything to dispel its allure. Zeal for the fabled arcadia lasted well until at the 1850s (and almost certainly afterwards).

During her visit to the Monte Rosa range, Elizabeth Warwick Cole discovered that one of her guides, Gaspere, avidly believed in the lost valley, the legend of which he had been “taught when a child”. The spot, Gaspere explained, was once accessed by two hunters who used a subterranean passage as their entrypoint. As in Saussure’s account, their success was short-lived. After their first journey, a “sudden” a surge of glacial water flooded the tunnel, stopping all further access. “When we expressed our incredulity,” Warwick Cole wrote in A Lady’s Tour Round Monte Rosa (1859), “Gaspere seemed much hurt, and assured us that the last survivor of the two hunters had died in the village not much more than fifteen years ago, and that no one then doubted the truth of their assertion.”

Comparable–in a certain sense–to the myth of Atlantis, the Monte Rosa-Hohen-Laub narrative stands as a vivid reminder of mankind’s continued reverence for and fear of unknown. Much like the Himalayas, whose reputation was shaped in part by Nepalese and Tibetan religio-cultural traditions, Monte Rosa’s image was influenced by an already rich tapestry of Alpine folklore. A kind of Abominable Snowman, Hohen-Laub was, for at least a century, unseen but present. Always eluding discovery, it lived on in the wilder recesses of the popular imagination, lingering (to quote the geographer and clergyman Samuel William King) “among lovers of the marvelous”.

Like those mythical deities of the primeval age who shapeshifted to adapt to the times, Hohen-Laub has not wholly disappeared from view. Thousands flock to the Valais Alps each year in search for adventure. A select few, daring it all, spend entire days climbing in subzero temperatures just for a glimpse of that joyous vale beyond the veil. Theirs is not a quest for a literal paradise, but something else. The spirit-lifting whistling of rarefied wind, the satisfaction of treading on footprintless land, the sight of rosy snow-mists gliding across the dawn-lit summit; all these are Hohen-Laub as it exists today.

Want more stories? Check out our spin-off project, Godfrey’s Almanack.

1 thought on “Monte Rosa and the Lost Valley of Hohen-Laub”