FANTAST IN FOCUS: DARRAN ANDERSON

Mythic cities, such as Atlantis and El Dorado, never really vanish. They’re as old as the human imagination itself and derive from ideas that are constantly evolving alongside humanity’s changing perceptions of the cosmos. The mind seems boundless, which means that any study of its ‘metropolises of fantasy’ is always going to be a Sisyphean labour. And yet, Darran Anderson charts these phantom lands with apparent ease. His latest book, Imaginary Cities (a whopping 560 pages), “roams through space, time and possibility, mapping cities of sound, melancholia, and the afterlife, where time runs backwards or which float among the clouds”. We caught up with Darran to learn more about his work with real and fictional mindscapes.

The Custodian: How’d you come up with the idea for Imaginary Cities?

Darran Anderson: A few years ago, I was living in Phnom Penh in Cambodia, helping a friend out with a film he’s been making. One evening I was drinking on the roof of the Foreign Correspondents’ Club and talking to an architect about a mutual interest in Antoni Gaudi, who I’ve loved since I was a child. It was rainy season so as the sun set these colossal electrical storms began moving in from the horizon towards the city. And it struck me that this place was more extraordinary than virtually anything I’d read in fiction, even sci-fi. Here was a city built on a river that occasionally flows backwards, a city that had been completely emptied during the reign of the Khmer Rouge, that had seen dystopia first-hand and somehow survived to become this strange terrible wonderful place.

The more I thought about it, the more fascinated I became with the border between real cities and imaginary ones and how each seeps into the other. So I wrote a short piece on the subject for 3:AM Magazine, thinking it was just a momentary obsession, but it’s kept growing. And it’s kept going further and further into different directions from reading Italo Calvino, watching Sans Soleil, looking at medieval maps and so on. The first draft of the book ran to about 1500 pages. It was ludicrous. You could carry it around in a briefcase. So I think the book is the first chapter in a vast endless project I’m now condemned to undertake, to answer for sins in some past life.

C: Amazing descriptions of fantasy worlds have come to us through poets like Ludovico Ariosto and H.P. Lovecraft. You also have a solid background in the poetic arts. To what extent would you say topography affects literary expression?

D: I think it does to a huge and under-acknowledged degree. We accept it readily when it comes to nature writing, which is why that genre is so rich. You read W.G. Sebald or Charles Bruce Chatwin or whoever and it’s clear that the landscape is saturated with history and stories but it requires the narrator’s knowledge and involvement. It seems to be how we perceive the world, in terms of symbols and resonances; we’re memory-obsessed pattern-seeking creatures. Despite periodic reminders to the contrary (Apollinaire’s poem Zone, the Beats, punk, hip-hop, psychogeography, and so on), there seems to be a reluctance to treat the city in the same way. The poets are forever fleeing into the countryside but, contrary to what Plato suggested, we need poets here, in the midst of buildings. The city is a huge memory theatre and we need ushers, guides, translators.

C: Some would say that cities and landscapes shape aspects of culture. In your research have you found that urban architecture (real and imaginary) can also be shaped by things like music and food?

D: Undoubtedly, you see it everywhere but take an obvious example like the Sydney Opera House, which we’re so used to seeing that we often forget how odd it is; a semi-nautical, semi-organic expressionist palace built around sound. This works in both directions; the course of music as David Byrne points out in his excellent How Music Works has been profoundly shaped by the buildings in which it has been played, from riverboats to stadiums.

There are intriguing parallels and intersections between architecture and music particularly. Johann Wolfgang Goethe famously wrote that architecture was “frozen music” and the old tongue-in-cheek line about shoegaze music was that it was “cathedrals of sound”. When Karl Teige attacked Le Corbusier, it was for drafting “an unrealizable utopia”, what he disdainfully called “future-music”. Certain critics rail against any hint of ‘architecture for architecture’s sake’; it suggests pleasure, indulgence, decadence. Buildings have to have function, or else they’re relegated to follies, but I think even the most rationalist and austere architect has a glimmer of aestheticism in them somewhere. They know, deep down, that the sound of a choir in a Gothic Church, for example, goes beyond reason.

What interests me about this relationship is where it might conceivably lead as technology continues to develop. It’s possible to envisage a day when architecture is built for the hell of it; buildings that are temporary, buildings that change according to our whims or chance. We might appreciate architecture as we do music today (just as we might one day inhabit music). There are already precedents. Steven Holl’s Stretto House was inspired by Béla Bartok’s Music for Strings, Percussion and Celeste while Iannis Xenakis’ Philips Pavilion was built according to the shape of distorted sound waves from Edgar Varèse’s Poème électronique.There’s a great sequence in Godfrey Sweven’s Limanora, where he describes a building material that shapes itself according to whatever music is played; so you can build different structures using melodies. These are fanciful ideas of course but perhaps the time has simply not arrived yet (we arrogantly assume we are at the conclusion of a linear idea of progress).

One very pertinent matter that we can look at, is how and why we have allowed commerce to take over our entire skylines (and indeed most of the territory of our cities). It’s a case of apathy and cowardice. We’ve allowed ourselves to be fooled into thinking that the towers that dominate our cities have to be those of finance, and not innumerable other subjects; the Tower of Philosophy that Hugh Ferriss envisaged for example or the Temple of Music sketched by Robert Fludd. A bit of Mammon-worship has a certain charm but to see it taking over everything is banal, to say the least, and demonstrably dangerous.

C: You’ve probably already fielded plenty of questions about Inception, but is there anything in your book about the ways we navigate dream worlds?

D: I think the only tangible interest of dream worlds is in how they connect to reality. The sense of the recognisable being distorted. There’s something about seeing the immediately identifiable streets of Paris being folded up that dazzles. There are few things however more tiresome than listening to someone describe their dreams but it’s intriguing to try and decipher where dreams come from and how they might influence our perception of the waking world. When I was a boy, my father would wonder aloud, often about dreams, “Are the people in dreams people you’ve met previously? Are they pieced together or completely invented?” It leads you to question if we can invent something entirely originally, like the idea of a new colour, or is everything supposedly original a kind of collage? We’re uncomfortable with the idea of culture as an echo-chamber because we cling to myths of the lone genius but the idea that we’re receivers as much as transmitters leads us to much more interesting places (those explored by the writer Tom McCarthy for example).

Aside from their lives and iconographies, I have a recurring fascination with the Surrealists for two reasons. One is that they seemed to revitalise a very old idea of portents, that secret messages about the future could seep out of dreams, coincidences, symbols and so on. This makes them maddeningly esoteric but it does suggest they were edging towards some semi-mystical conception of cybernetics. Secondly they tried to give the sleeping world an equivalence to the waking world, which isn’t quite as daft as it sounds. There’s a radical sceptical tinge to it; everything in the world that we are told is immovable can be questioned and reimagined. It begins as a parlour game or dream interpretation but, in the right hands, it can show us that the solid is not quite as solid as it seems, and how much economics, the way we measure time, morality etc are the result of decisions, prevailing prejudices and leaps of faith. So there’s more to Surrealism than optical illusions.

We have to look at the limitations of dreams too, and their mechanics. I’m going to break my rule of retelling dreams but I had one recently where I was avoiding someone tiresome and, in the dream, I darted into a shop and then upstairs and the dream strangely didn’t keep pace with this. When I got to the top of the stairs and looked around at this balcony, it was so badly constructed that it wrecked the suspension of disbelief and made me suddenly aware that it was a dream and I woke up. It was like this odd Brechtian moment but it’s a reminder that if we’re to learn anything from dreams it’s as much from their banality and dislocation as their extravagance.

C: Have you had a chance to try Oculus Rift? What’s your opinion on the future of video games and the exploration of virtual metropolises?

D: Not yet but I’m studying it at the moment. I hope to soon. In a way, it’s surprised me how long the idea’s taken to really take off. I remember trying on a virtual reality headset in a bowling alley in Belfast in the early 90s and thinking it would instantly change everything and it didn’t; it felt a bit like all those jet-pack futures promised in the 50s.

It’s clear though that the border between cyberspace and real space will increasingly blur. It’s already happening. We have to consider what these mean for ideas of power, autonomy, and freedom. Essentially, it’s the opening up of new battlefields; there will be innovations and tyrannies, resistances, reactions, and side-effects, and we need to be ready even one step ahead. These are old concerns going back to Plato’s Cave at least but they are vitally important ones. It’s immensely exciting, but it is imperative that the technology needs to work for us and not against us. It’s all too easy to imagine glittering virtual metropolises as escapes from increasingly miserable real-life ones. We need to make progress in both.

C: What are your five favourite pre-Modern illustrations of fictional architectural structures? Does Giambattista Piranesi make the list?

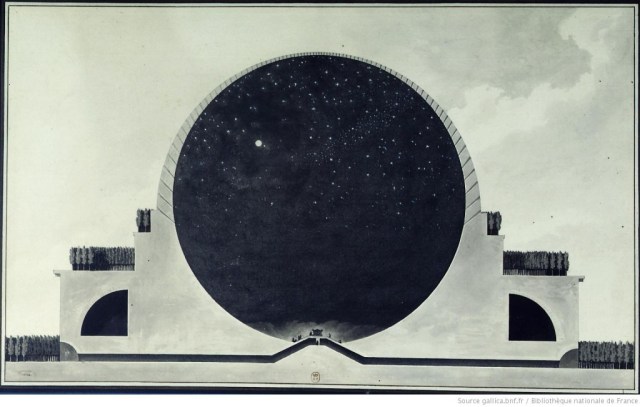

D: I like Piranesi a lot. I have a section in the book looking at his Carceri d’invenzione and the connections of Gothic architecture to the rise of empire and industry, which was not coincidental. The strange thing about the past is that more and more of it appears to be being unearthed when the truth is likely the opposite. Choosing favourites is always momentary, it changes all the time but the first that spring to mind are Étienne-Louis Boullée’s Cénotaphe à Newton, The Temple of the Rosy Cross, the weird space city in the background of Hieronymus Bosch’s Adoration of the Magi, Baba Yaga’s chicken-legged hut by Ivan Bilibin and dozens of Towers of Babel (let’s pick one of Pieter Breugel’s). The list is endless though, you could have so many Japanese ukiyo-e or mythic buildings from virtually any mythology on the planet. The joy is in the exploring rather than the cataloguing.

C: What are your upcoming projects?

D: I’m starting work on a book looking at the relationship between video games and architecture, which will hopefully find a sympathetic publisher; games are bigger than Hollywood and yet there’s been a ridiculous lack of mainstream critical attention paid to them (there’s no shortage of great writing and insight within the gaming world itself). I’m also working on a mythological travel guide to real places. I have a poetry collection based on a Jorge Luis Borges-inspired rewriting of Irish history called The Ghost Republic. Most importantly, I have a tiny baby son; he’s the main ongoing project.

Darran’s book comes out 16 July. You can pre-order it here. For more on Darran’s other projects, check out his website.

1 thought on “Fantast in Focus: Darran Anderson”